INTRODUCTION

Among the many visual determinants of physical attractiveness, the face is of particular importance. Its proportions and contours vary depending on the sex, race, ethnic group and age. Over the centuries, the concept of an attractive face has changed. The current beauty criteria are based on the universal laws of aesthetics, including symmetry and proportions, although it should be emphasized that there is no consensus on what constitutes facial beauty [1]. Unlike other parts of the body, one’s face can only be viewed and analyzed indirectly by looking at its reflection in a mirror or at a photograph. As direct observation is impossible, the perception of one’s face and its constituting elements differs from the perception of other parts of one’s body that are visually perceptible, such as the abdomen, arms or thighs [2].

In some mental health conditions, an individual’s perception of his or her face is disturbed. Such discrepancies between the actual and the expected appearance of one’s own body are observed, among others, in patients with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) and anorexia nervosa (AN) [2-4]. Both disorders involve an incorrect perception of one’s body. In BDD, the preoccupation is most frequently with the skin, hair, or nose, although any body area may be involved. While facial features are commonly the subject of concern, BDD can also present with worries about muscle size or tone (bigorexia), or about other body parts [4, 5].

AN is characterized by a distorted perception of body weight and shape, along with an intense fear of gaining weight and behaviors that hinder weight gain. Individuals with AN often have distorted views of their abdomen, thighs, and arms [4-7]. However, recent studies have indicated that they may also have skewed perceptions of their faces. Many patients report dissatisfaction with the size or proportions of their facial features, even when these are symmetrical and proportionate [2, 8]. The distortions may reflect broader cognitive and emotional challenges faced by patients with AN, such as perfectionism, difficulties in identifying and expressing emotions (a condition known as alexithymia), and low self-esteem [8, 9]. Theoretical frameworks, including the cognitive-behavioral model of eating disorders and embodiment theory, suggest that body image distortions in AN are a complex phenomenon that includes perceptual, emotional, and cognitive elements [6-9]. Moreover, some publications have reported a negative correlation between body mass index (BMI) and the perception of facial attractiveness or shape in female patients with AN. Specifically, lower BMI has been associated with more critical evaluation of one’s face and also the perception of the faces of others as less attractive [2].

Considering the significance of the face in self-identity and interpersonal interactions, along with the perceptual, emotional, and sociocultural factors involved in AN, facial perception emerges as an important yet underexplored aspect of body image distortions. Investigating this area could provide valuable insights into the complex psychopathology of AN, extending beyond conventional concerns about body size. This may, in turn, help enhance both diagnostic practices and treatment strategies.

This study aims to compare the AN patients’ subjective assessments of their face, including its shape and dimensions, with the parameters obtained in the morpho-metric examination. This complex research focused on the following specific objectives: 1) patients’ facial symmetry evaluation based on a direct analysis by a dentist; 2) the relationship between the patient’s BMI and degree of subjective satisfaction with the shape and size of their faces; 3) the objective dimensions and shape of the AN patients’ faces based on the morphometric test; and 4) the relationship between the type of face shape defined by the morphometric test parameters and the subjective degree of patient satisfaction and their desire to change their facial appearance.

METHODS

Anorexic female patients were invited to participate in the study. They were diagnosed with AN in accordance with the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders in DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) [4]. The exclusion criteria for this study included the presence of other systemic or chronic medical conditions, such as endocrine, autoimmune, or metabolic disorders. Additionally, individuals diagnosed with psychotic disorders or severe psychiatric comorbidities that could compromise cognitive or perceptual functioning were also excluded. We recognize that the term “systemic diseases” is broad and can be a topic of ongoing debate. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, we have used a practical clinical definition, referring specifically to multisystem or chronic medical conditions that require medical management.

The clinical characteristics of the participants were collected through their medical records and clinical interviews. The survey included questions about the patients’ perceptions of the shapes and dimensions of their faces as well as their desire to change them. A custom-designed questionnaire was implemented to assess the participants’ self-perceptions of their facial features. The questionnaire consisted of a series of closed-ended questions focused on individuals’ subjective satisfaction with the shape and size of their faces. The participants were specifically asked, “Are you satisfied with the shape and size of your face?” and provided with three response options: “Yes,” “No,” and “I don’t know.” Each patient who answered “No” was then asked if they would like to change their face, and if so, how they would like to change it (for example, “I would like my face to be slimmer”). The responses were treated as nominal categorical variables and analyzed accordingly in the statistical analysis.

Researchers who conducted the study had undergone training in accordance with the World Health Organization recommendations for anthropometric measurements [10]. The training included clinical examination of healthy children who were not included in the study. The k-value was 0.80, indicating a satisfactory level of concordance. The data obtained were recorded in purpose-designed charts. The clinical trials consisted of direct inspection and measurements of the patients’ faces.

During the examination, the patients sat in a comfortable position on the chair with the researcher in front of them. The girls were asked to keep a natural, relaxed expression on their face. In the first stage of the clinical trial, the symmetry of their faces in relation to the midline of the body (defined by skin points) was visually assessed. In the analysis, attention was paid to whether the unpaired midpoints lay on the midline and whether the paired, homonymous lateral points of the right and left sides were equidistant from it.

In the morphometric test, a sliding caliper and an ALUMET spreading caliper were used. After palpating the skin to standard anatomical landmarks, measurements were taken with an accuracy of 1 mm. Following standardized research techniques [11], each measurement was repeated three times. The mean value of the three measurements was then used for further analysis. The following distances, determined by the respective skin points, were measured:

1) morphological face height (FH), ranging from the nasion point (n), located in the largest nasofrontal depression, and the gnathion point (gn), located most inferiorly and anteriorly on the chin;

2) three thirds of the physiognomic face:

upper (frontal) – defined by the following points: trichion (tr), lying on the upper border of the forehead on the hairline, and ophryon (on), located on the upper eyebrow line,

middle (nasal) – defined by the following points: ophryon (on) and subnasale (sb), the skin point lying in the subnasal depression where the skin septum of the nose passes into the upper lip,

lower (maxillary) – from subnasale (sb) to gna thion (gn);

3) morphological facial width (FW), which is defined by the points farthest from the midline on the zygomatic arch: zygion (zy) – zygion (zy);

4) the width of the slit of the left and right eyes, limited by the outer exocanthion (ex) and inner endocanthion (en) corners of the eye;

5) the width of the mouth slit, i.e., the distance between the mouth corners: cheilion (ch) – cheilion (ch);

6) the width of the nose, defined by the most lateral points on the wings of the nostril: alare (al) – alare (al);

7) the distance between the outer corner of the eye slit and the outermost part of the auricle.

Then, based on the obtained data, the facial (prosopic) index was calculated as follows:

Prosopic Index (PI) = (morphological face height / morphological facial width) × 100

Based on the PI, the faces were classified as hypereuryprosopic (short and very broad, range < 79.9), euryprosopic (short and broad; range 80-84.9), mesoprosopic (medium or round; range 85-89.9), leptoprosopic (long and narrow; range 90-94.9) or hyperleptoprosopic (very long face, range > 95) [12].

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistica software programme, version 12 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, United States). The values of the qualitative variables are presented in cross-tabulation. Comparison between individual features was carried out using the non-parametric Pearson c2 test. Correlations between quantitative variables were analyzed using the Spearman test. The results were considered statistically significant at the significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

The study was approved by an independent ethics committee (nr 633/13), and it adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. After receiving an explanation of the study’s aim and procedure, the participants and/or their parents provided informed and written consent to participate in this study.

RESULTS

A total of 24 female patients diagnosed with AN participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 13 to 18 years old, with an average illness duration of 14.2 months (ranging from 3 to 36 months). Sixteen participants (66.7%) were experiencing their first episode of AN, while the remaining eight had reported at least one prior episode. At the time of assessment, ten girls were receiving inpatient treatment, while 14 were being cared for on an outpatient basis. On average, 3.5 months had elapsed since they achieved their current body weight, defined as BMI above 16.0 Although prior to inclusion in the study, all patients were diagnosed with AN according to DSM-5 criteria by a psychiatrist, not all of them met the underweight threshold based on raw BMI values during the anthro pometric assessment. This discrepancy likely reflects ongoing or recent therapeutic interventions and partial or full weight restoration.

Given that all participants were adolescents, their BMI was assessed using age- and sex-adjusted BMI-for-age percentiles and Z-scores, in accordance with WHO recommendations for individuals aged 5 to 19 [13]. A BMI-for-age Z-score below –2 standard deviations (SD) was considered indicative of underweight status. The mean BMI Z-score for the group was –1.78 (SD = 0.85), with 13 out of 24 participants (54.2%) presenting Z-scores below –2 SD. To provide additional clinical context, we also reported BMI classifications based on the DSM-5 severity criteria for AN. According to these, 14 participants were classified as underweight (BMI = 17.00-18.49), while ten were categorized as moderately underweight (BMI = 16.00-16.99). However, it is crucial to note that the direct application of these cutoffs may not fully reflect nutritional status in adolescent populations due to age-dependent growth patterns.

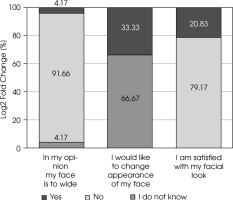

No deviations in facial symmetry relative to the mid-line were observed during the direct inspection of the faces of the female participants with AN. The faces of all the girls were found to be symmetrical. Statistical analysis of the morphometric examination results revealed no significant differences between the frontal, nasal and maxillary thirds of the face. Likewise, no significant asymmetries were found in the five vertical segments: the widths of the left and right palpebral fissures, nasal width, and the distances from the outer canthus to the most lateral point of the auricle on both sides (p > 0.05). The results of the questionnaire survey are presented in Figure I.

Statistical analysis revealed a relationship between the degree of satisfaction with facial shape and dimensions and the desire to change its appearance (p = 0.01). 79.17% of participants were not satisfied with their facial appearance. 66.66% expressed a desire to change it (45% of whom specifically wished for a slimmer face) while 33.33% responded ‘I don’t know” (Figure I). Among participants dissatisfied with their facial appearance, a higher proportion believed their face was too wide (87.5%) compared to those who were undecided (33.3%). This difference was statistically significant (χ2(1) = 5.20, p = 0.02).

No statistically significant association was found between BMI category (underweight vs. emaciated) and the subjective assessment of their facial shape and dimensions. Similarly, no significant association was found between participants’ age group and self-perception of facial appearance. As both variables were categorical, the data were analyzed using χ2 tests (p > 0.05 in both cases).

The mean value of the Prosopic Index (PI) was 94.27. Based on PI classification, three participants had a mesoprosopic (medium, round) face shape, four were classified as leptoprosopic (long, narrow), and three as hyperleptoprosopic (very long) (Table 1). No statistically significant association was found between face shape category and satisfaction with facial appearance (χ2 test, p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The acknowledged standards of beauty are based on harmony and proportions. A face is considered harmonious when it is symmetrical to the median plane that runs through all the midpoints and divides the face into two parts: right and left. The human face, like the rest of the body, is bi-laterally symmetrical, except that it is not perfect symmetry. In the population at large, a tendency toward asymmetry is observed [1]. This phenomenon is known as directional asymmetry, where the divergent values of a given feature between the two halves of the body are systematic, i.e., one of the sides (left or right) displays a greater measurement. This type of asymmetry is common in many facial features – for example, most people find the left side of their face to be larger than the right. Asymmetry can also be an individual feature, representing the so-called fluctuating asymmetry (FA). In such cases, the degree of asymmetry differs from typical population-level patterns and is considered a manifestation of developmental instability [1, 14]. Direct inspection of the faces of participants with anorexia showed no visually noticeable FA (i.e., no deviations in the size or position of the paired structures were detected, which is attributed to population-level asymmetry). According to the researchers, the faces of all the girls were symmetrical [1].

Table 1

Face shape and facial index in examined patients

Apart from symmetry, facial harmony also requires proportionality, both vertically and horizontally. According to the “golden division of the face” rule, the face is divided into three equal fragments: the frontal third (trichion – ophryon), the nasal third (ophryon – subnasale) and the maxillary third (subnasale – gnathion). Moreover, a face is considered to be proportionate when it complies with the “rule of five”, according to which the face is divided into five equal parts. The width of the eye slit should be 1/5 of the face width, similarly to the width of the nose and the distance between the outer corner of the eye slit and the outermost part of the auricle [1].

In our study the girls with anorexia did not show statistically significant differences in the dimensions of individual horizontal facial fragments. This suggests that the facial proportions, both horizontal and vertical, were preserved. Based on visual symmetry analysis and the measurements of individual facial segments, the faces of all the girls enrolled in the study were deemed harmonious (i.e., both symmetrical and proportionate).

Despite the objective findings, the results show that the female anorexic patients were critical of the shape and dimensions of their faces. Importantly, this dissatisfaction did not correlate with age or BMI. Seven out of eight patients who were dissatisfied with their face appearance expressed a desire for a slimmer face. Moreover, the girls who were dissatisfied with their facial appearance were statistically more likely to think that their face was too wide. However, the PI showed that none of them had a wide face. Instead, facial classification revealed that the girls had medium-wide, narrow or very narrow face shapes.

Based on the morphometric tests and the proportionality index (PI), the patients’ concerns about their faces being too wide – and their desire for a slimmer facial appearance – appear to be unjustified. These findings suggest that individuals with AN exhibit a distorted perception not only of their bodies, including their face, viewing them as wider than they objectively are.

To date, facial perception in individuals with AN has not been studied in combination with objective analyses. Previous studies have typically focused, among other aspects, on the evaluation of facial photographs, either of oneself or of strangers. Moody et al. [3] compared anorexic female patients’ perceptions of their faces in black-and-white photographs with healthy subjects’ perceptions of the same photos. In all the photos, the faces showed a natural expression and depicted people of various ages and body weights. The results revealed that, although the face appearance was not the central problem of the anorexic patients’ clinical picture, they rated the faces as less attractive compared to the evaluation of the same faces by healthy people. The authors suggested that individuals with anorexia may project their own self-image onto the faces they view, interpreting facial shape and dimensions – which may serve as cues to body weight – as triggers for critical evaluation.

Similarly, Blechert et al. [15] found that individuals with anorexia were more critical of photos of their own faces than of unfamiliar faces. The authors attributed this to broader body dissatisfaction reinforcing the notion that distorted self-perception extends to facial features. This critical attitude was focused on the shape and size of the face. Although the literature does not report facial perception being a main problem of girls with AN, research increasingly suggests that the perception of this part of body image may also be impaired [6-8, 14].

The findings from our study reveal a notable discrepancy between morphometric analyses of facial features and subjective assessments of appearance. This observation is consistent with existing literature on healthy populations, which also shows that self-assessments of facial appearance often diverge from evaluations made by others and from objective standards. This phenomenon, commonly known as self-other asymmetry, may be partly explained by the mirror exposure effect, whereby individuals become accustomed to seeing their reflection, which can lead to distorted perceptions of their ownphotographic images [16]. Furthermore, healthy individuals – particularly women – tend to more critical of their appearance compared to images of others, a tendency linked to internalized beauty ideals and predisposition for social comparison [17]. While similar psychological mechanisms are likely at play in individuals with anorexia, they appear more pronounced and are accompanied by additional cognitive and emotional challenges, such as perfectionism, low self-esteem, and alexithymia.

In contemporary mass media culture, the ideals of facial beauty and attractiveness are largely created by the media – often based on advanced image-enhancement techniques, including makeup and digital photo processing. This creates an ideal modern female face that is rarely attainable in the real world. Such imagery can heighten critical self-evaluation. For individuals with AN, these pressures may be especially significant. The internalization of unrealistic beauty ideals in combination with emotional, cognitive, and personality disorders are prevalent in this population, including perfectionism, low self-esteem, and alexithymia. A distorted perception of one’s appearance, particularly concerning the face – an essential aspect of identity and social interactions – can exacerbate negative self-image and contribute to interpersonal challenges.

CONCLUSIONS

This study leads to three primary conclusions. First, the majority of female patients with AN included in our study expressed dissatisfaction with the shape and size of their face, despite the absence of objectively measurable deviations in facial symmetry or proportions. Many indicated a desire to change their facial appearance. Second, based on the findings, it can be assumed that anorexic patients have disturbed facial perception and perceive their faces as wider than they actually are. Third, no significant association was found between facial dissatisfaction and BMI, indicating that individuals with AN may have a distorted perception of their facial features, regardless of their current body weight. This suggests that these perceptual distortions are more closely linked to cognitive and emotional factors rather than to physical characteristics alone.