Introduction

An outbreak of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 started in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and in March 2020, it was declared by the World Health Organization as a global pandemic [1]. Almost 3 years into the COVID-19 pandemic, what was initially seen as a respiratory disease [2] is now known to be a disease involving many organs, including liver hepatic dysfunction, with the possibility that it may have long-term consequences for the patients. In our previous systematic review (SR) [3], we were able to show that liver abnormalities were present in other Coronaviridae infections (including Middle East respiratory syndrome – MERS and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus – SARS) as mild to moderate elevation of transaminases, hypoalbuminemia and/or prolongation of prothrombin time. However, the clinical importance of this phenomenon required further elucidation.

Standard laboratory liver tests are used as biomarkers of liver function and disease severity, including elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (above 40 U/l), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (above 40 U/l), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGTP) (above 49 U/l), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (above 135 U/l), total bilirubin (above 17.1 µmol/l) [4]. Most studies showed elevated levels of ALT and AST in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients [5]. Ding et al. [6] have demonstrated that AST and direct bilirubin were independently associated with mortality in COVID-19. According to Fan et al. [5], levels of prealbumin and albumin, ALP, GGTP, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and total and direct bilirubin were associated with disease progression in COVID-19.

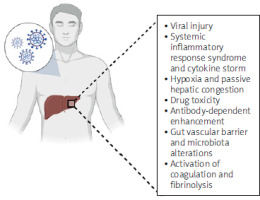

As previously shown in our SR, histopathological findings varied between non-specific inflammation, mild steatosis, congestion, and massive necrosis [3]. The mechanism of liver dysfunction in COVID-19 is multifactorial. It includes: i) viral injury due to hepatotropic action with viral hepatitis due to replication and, ii) systemic inflammatory response syndrome and cytokine storms. SARS-COV-2 shows hepatotropism, with the highest gene expression levels for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, sinusoidal endothelial cells and liver cells, as shown by RNA sequencing [7]. This process might be increased by inflammation, liver damage and altering viral receptor expression, with ACE2 being recognized as an interferon-inducible gene in human respiratory epithelial tissue [8].

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is induced by inflammatory cytokine storms that cause acute systemic cell destruction, liver necrosis, and severe organ damage [9]. In COVID-19, the levels of interleukin 2 and 6 (IL-2 and IL-6) are elevated in the serum of patients with unfavourable clinical outcomes [10]. Secretion of tumour necrosis factor-α, IL-2, IL7, IL-18, IL-4, and IL-10 increased pro-inflammatory cells (CCR4+CCR6+ Th17), which was more prominent in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) as compared to less severe infection [11].

Another mechanism of liver damage in COVID-19 may be associated with hypoxia secondary to respiratory failure and passive hepatic congestion related to mechanical ventilation and high levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) leading to ischemia [12]. This leads to hepatocyte dysfunction due to glycogen consumption, lipid accumulation, and depletion of intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP), further suppressing cell survival signals and liver cell death [13]. Moreover, drug toxicity and immune response via virally induced intrahepatic cytotoxic T cells and Kupffer cells must also be considered. Antibody-dependent enhancement may be another pathogenetic mechanism [14]. These antiviral antibodies are used by SARS-CoV-2 to enter macrophages, granulocytes, and monocytes through a non-ACE2-dependent pathway, causing overwhelming replication inside these immune cells and disease progression leading to liver injury [15]. Another way includes alterations of the gut vascular barrier and microbiota [16] and activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis resulting in thrombocytopenia [14]. Moreover, liver injury in COVID-19 has been regarded as a severe consequence of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) [17], with varying degrees of hepatotoxicity associated with different agents, but also visible as reversible injury after withdrawal of these medications. The pathological mechanisms in COVID-19 can be described as multi-hit theory, with multiple underlying mechanisms – direct SARS-CoV-2 effect on hepatic cells, hepatic hypoxia, hepatic ischemia, cytokine-storm related, as a consequence of gut-liver axis derangement, as well as DILI [18]. This is why identifying the changes at an early stage of the pandemic seemed especially important and informative for conclusions as guidance for future Coronaviridae outbreaks. Potential mechanisms for liver injury are summarized in Figure 1.

Having previously shown that Coronaviridae infections are associated with liver damage, we carried out a SR and meta-analysis at an early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic to determine whether SARS-CoV-2 infection affects the level of liver-produced molecules: ALT, AST, GGTP, bilirubin, total protein, albumin, and prothrombin (with INR). We hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 alter the abovementioned at a mediocre level.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

At an early stage of the pandemic, ten authors (A.B., J. S-P., D. M-M., G.K., H.W., L.L., M.M., M. Kaczmarczyk, M. Kukla, P.S.) independently searched (using Google engine) PubMed and Embase from their inception until 04/03/2021 with language restriction (only English) for full-text, published, observational studies aiming to evaluate whether SARS CoV-2 infection affects the level of liver-produced molecules. The early search was intentionally performed to identify changes related to initial variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Studies in adult humans (≥ 30 subjects) reporting any of the following outcomes: ALT/AST/GGTP/ bilirubin/total protein/albumin/INR/prothrombin were eligible. We included full-text studies in which the aim was liver damage. The search strings we used are listed in Supplementary Table SI. The study protocol was registered in the Prospero database under accession no. CRD42021242958. The early search of ours was intentionally performed to identify changes related to initial variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the pre-vaccination stage. The electronic search was supplemented by a manual review of reference lists from eligible publications and relevant reviews.

The exclusion criteria were: review articles, commentaries, editorials, and letters to editors, case reports, case series, article on the paediatric population, no information on the local ethics committee approval.

Data analysis

Data on study characteristics, including design and risk of bias, patient socio-demographic data with comorbidities from each study was independently extracted by researchers following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [19] standards in duplicate; however, as for the high number of eligible studies, the extraction process was done by all authors involved in the screening process. Authors were contacted for additional information twice, 2 weeks apart, whenever data was missing for the review. Consensus resolved inconsistencies, with senior clinicians (W. Marlicz and M. Kukla) involved. Data from each stage was gathered in a tabular form using Excel file. Bibliographic data was managed using Zotero software.

Outcomes

Co-primary outcomes were ALT/AST/GGTP/bilirubin/total protein/albumin/INR/prothrombin in either raw data or expressed as elevated/diminished regarding physiological values.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We conducted a random-effects meta-analysis to synthesize the data from outcomes where at least two studies contributed relevant information, utilizing Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V4 software. To assess the variability among the included studies, we applied the χ2 homogeneity test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05 indicating substantial heterogeneity. All statistical analyses were performed as two-tailed tests, with an α level set at 0.05.

For continuous outcomes, we calculated pooled means based on either the final endpoint scores (which were preferred) or the change from baseline to endpoint, using data from observed cases (OC). This analysis included only studies that provided both means and standard deviations (SDs), ensuring consistency by unifying measurement units wherever possible. For categorical outcomes, we determined the pooled event rate across studies.

The results of the meta-analysis were presented both visually, using forest plots, and in tabular format for clarity. Additionally, to assess the potential impact of publication bias on our findings, we examined funnel plots and conducted Egger’s regression test. We also applied Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method to adjust for any detected bias. The final results were summarized in detailed tables and illustrated with representative figures to enhance understanding.

Risk of bias (ROB)

Each researcher independently evaluated the risk of bias (ROB) in the included observational studies using the New Ottawa Scale [20]. This scale assesses several key aspects of study quality, assigning a star for each criterion met. The criteria cover areas such as selection, comparability, and outcome assessment. The final score for each study is the sum of stars, with a maximum possible score of 9 stars. A higher total score indicates a lower risk of bias and, consequently, a higher quality of the study. This systematic approach ensured a consistent and objective assessment of study quality across the included studies.

Results

Search results

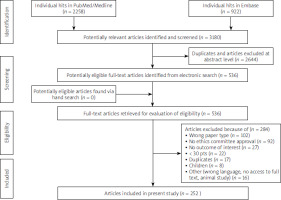

The initial search yielded 3180 hits. Two thousand six hundred forty-four (n = 2644) studies were excluded as duplicates and/or after evaluation on the title/abstract level. No additional articles were identified via hand search. A total of 536 full-text articles were reviewed. Of those, 284 were excluded due to not fitting/because they did not meet inclusion criteria. Primary reasons for exclusion were either the type of paper (n = 102; i.e., review, systematic review, meta-analysis, letter to editors or correspondence with no clinical data) or no data on approval by the bioethics committee (n = 92). Other reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 2. Overall, the search strategy yielded 252 studies included in the meta-analysis.

Study and patient characteristics

The collected data was as follows: publication year, study location, sponsorship, setting, focus of the study, patient characteristics, and comorbidities. The analysis included 252 observational and retrospective studies with 104693 adult patients. When a study reported outcomes in several groups, these were merged, and appropriate measures were calculated if possible. When not, data was presented separately for each of the subgroups. The mean/median age varied between 38 and 69 years. In 113 studies, a total of 6210 (5.9%) patients had pre-existing liver disease, among which HBV and chronic liver diseases were the most frequent. Other comorbidities were also reported, among them/including diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. More data is presented in Supplementary Table SII.

Risk of bias (ROB)

The mean number of ROB stars in the NOS scale in all studies included in the meta-analysis was 6.8 (median = 7). There were 11 studies with the highest number, i.e., 9 stars and 4 studies with the lowest, i.e. 3 stars. Details of ROB evaluation are given in Supplementary Table SIII.

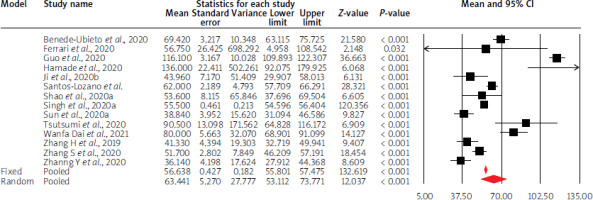

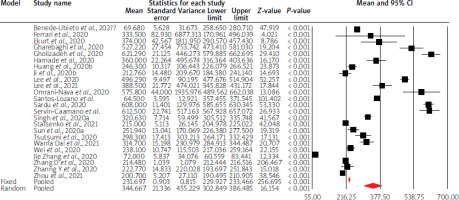

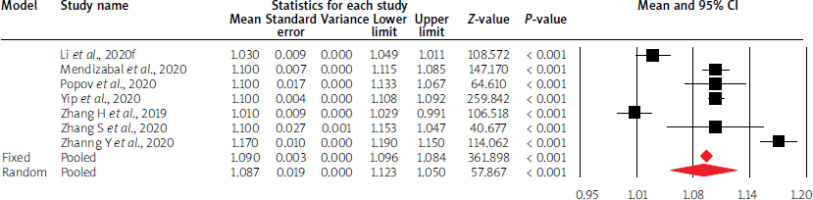

Effects on quantitative liver parameters

Using random-effects weights, the overall mean liver parameter values were not altered compared to physiological values, except for GGTP, LDH activity, and INR values. Moreover, in the case of AST, ALT and albumin levels, mean point estimates were close to limit values of standards. The details are given in Table I and Figures 3–5.

Table I

Point estimates for mean values of evaluated liver parameters

Overall, an Egger’s test suggested a publication bias mean for AST (Egger’s test: p = 0.01), bilirubin (Egger’s test: p = 0.0001), LDH (Egger’s test: p = 0.01), albumin (Egger’s test: p < 0.00001). The Duval and Tweedie’s method adjusted values for respective parameters as follows:

Effects on the prevalence of abnormal liver parameters

Using random-effects weights, the overall event rate of abnormal liver parameters as compared to physiological values ranged between 0.097 (bilirubin) and 0.52 (total protein). The details are given in Table II. Raw data, including information authors considered abnormal levels is placed in Supplementary Table SIV.

Table II

Point estimate for event rates on abnormal liver parameters

Overall, an Egger’s test suggested a publication bias for the rate of abnormal AST (Egger’s test: p = 0.000011), ALT (Egger’s test: p = 0.00000) and INR (Egger’s test: p = 0.005). The Duval and Tweedie’s method adjusted values for respective parameters as follows:

AST: 13 studies to right of mean; random model point estimate: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.25–0.32, Q value = 3018.42.

ALT: 14 studies to right of mean; random model point estimate: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.24–0.30, Q value = 2005.04.

INR: 1 study to right of mean; random model point estimate: 0.15; 95% CI: 0.06–0.32, Q value = 124.46.

Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic significantly impacted the health and well-being of millions of people [21]. Aside from mortality ascribed to the initial infection, SARS-CoV-2 showed a major impact on multiple organs/systems, especially in patients with acute and/or chronic liver disease. SARS-CoV-2 infects the GI tract through the ACE2 receptor, which, apart from the respiratory system (represented in relatively small amounts, mainly on type II alveolar epithelial cells), is also present in ileal enterocytes, in the colon epithelium, in the liver, proximal renal tubule cells, oral epithelium, especially along the tongue, thyroid gland, cardiac muscle cells, stem and progenitor bone marrow cells and testes [3, 22].

We and others previously showed that patients with COVID-19 presented with mild to moderately elevated liver transaminases, hypoalbuminemia and prothrombin time prolongation followed by non-specific inflammation, mild steatosis, congestion, and massive necrosis in liver biopsy specimens [3]. SARS-CoV-2-associated liver damage is multicausal, including a direct effect of the virus on hepatic cells, systemic inflammatory response due to cytokine storm, hypoxia and hypoxemia, drug-induced hepatic injury, and alterations of gut-liver axis. The incidence of liver injury in COVID-19 patients ranges from 15% to 60% and is a crucial factor contributing to liver dysfunction [3].

The current systematic review and meta-analysis focused on determining whether SARS-CoV-2 infection influences liver function tests. We could document that the overall mean values of liver parameters were not altered compared to physiological values, except for GGTP, LDH, and INR values. Moreover, the mean point estimates were close to the mean normal values for AST, ALT, and albumin levels. During COVID-19, important indicators of liver damage are the ALT, AST, ALP, GGTP and bilirubin levels.

Based on the activity of individual enzymes, the following types of liver damage can be distinguished: i) hepatocellular (ALT and/or AST activity 3 times above the upper limit of normal (ULN) or AST/ALT activity greater than ALP/GGTP activity (20.75%); ii) cholestatic (ALP and/or GGTP activity 2 times above the ULN or ALP/GGTP activity higher than AST/ALT) (29.25%); iii) mixed (AST and/or ALT activity 3 times above the ULN and ALP/GGTP activity 2 times above the ULN) (43.4%) [23].

It was elegantly shown that patients with hepatocellular and cholestatic types had almost three times higher risk of severe COVID-19 compared to those without abnormalities in liver test results. The mixed type increased the probability of developing a severe form of the disease by more than four times. Abnormal liver enzyme levels occurred in 41% of patients on admission, increasing to 76% of patients during hospitalization. Liver damage (defined as AST and/or ALT levels 3 times the ULN and ALP/GGTP levels 2 times the ULN or bilirubin 2 times above the ULN) occurred in 5% of patients and increased to 21.5%, respectively. An adverse impact on the progression of COVID-19 is the development of mixed types of liver damage during hospitalization and the development of liver damage, which will significantly increase the risk of severe COVID-19 [4].

Abnormal liver test results were also associated with abnormal results of other laboratory evaluations, including a more significant difference in the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli and arterial blood, increased LDH, higher ferritin and glucose levels, and lower albumin levels [24]. This may indicate a direct impact of the virus on the synthetic function of the liver. Patients with abnormal liver parameters also showed immunological disorders manifested by reduced numbers of CD4 + T cells, B cells and NK cells. Interestingly, IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) were not altered [24]. Aminotransferase activity was also related to mortality and hospitalization time [25]. The overall mortality rate in patients treated for COVID-19 is 2.6%. In patients with abnormal liver enzyme activity, the mortality rate was 4.7%, compared to patients with normal liver function (1.1%). Moreover, hospitalization time in patients without liver damage was significantly shorter (15 days) than in patients with abnormal liver test results (19 days) [24].

However, liver damage in COVID-19 may also be drug-induced [17]. Based on the analysis of patients treated with antibiotics, antivirals, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), no differences were found in those with normal and abnormal transaminase results. Therefore, there is no evidence that the use of these drugs increases the risk of liver damage. Notable exceptions are lopinavir and ritonavir. When they were used, the risk of liver damage increased four times [26].

SARS-CoV-2 may cause reactivation of chronic hepatic disease with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) that has been shown to occur in 10–30% of all hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Patients with pre-existing liver diseases are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infections and have a worse prognosis [27]. Chronic liver disease, diabetes or hypertension significantly worsen the course of the disease [28]. The highest risk of severe disease occurs in patients with alcoholic liver disease [29].

In patients < 60 years of age with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), almost three times higher risk of the severe course of the disease was observed. The mortality rate was the highest in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C), ranging up to 51%. The risk of mortality increases with the progression of liver failure: Child-Pugh A – 1.90, Child-Pugh B – 4.14, Child-Pugh C – 9.32 times [30]. At the same time, liver cirrhosis increases the risk of mortality regardless of patient age. The increased risk of death in COVID-19 patients with liver cirrhosis was mainly associated with the development of respiratory and cardiovascular complications. It has also been shown that COVID-19 patients with cirrhosis require more frequent ICU admission and renal replacement therapy [31].

Hepatic involvement may be suspected when abnormalities in the levels of liver enzymes and/or concurrent radiologic findings are present, both of which can be utilized to predict patient prognosis. When analysing laboratory values, a combination of elevated GGTP, AST, ALT and hypoalbuminemia may indicate a severe degree of liver injury and be a good predictor of intensive care unit admission. Conversely, liver computed tomography (CT) attenuation and a lower liver-to-spleen ratio both indicate a more severe illness [32, 33].

Our analysis has limitations, mainly due to the high heterogeneity of the included studies. Moreover, laboratory parameters included by us may be a partial list of possible evaluations or ratios used in clinical practice. Apart from laboratory findings, organ imaging using ultrasound or CT and/or liver biopsy specimens should be used and evaluated to accelerate the diagnosis and find patients at risk of fulminant hepatic failure. Therefore, future studies could include laboratory findings and imaging-based or biopsy evaluations. We may not exclude that patients probably infected with other virus variants than those currently present were included in our meta-analysis. Still, considering the relatively lower virulence of the virus variants existing so far, this is not of great clinical significance. At last, our screening algorithm might have missed some studies with the focus of interest of the present SR.

Conclusions

Abnormal levels of liver enzymes occur in a significant group of patients with COVID–19 and are related to disease severity. Overall, in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the mean values of liver parameters were not altered as compared to physiological values, except for GGTP and LDH activity and INR values. Moreover, AST, ALT and albumin level mean point estimates were close to limit values of standards. These laboratory findings may be helpful in future prognosis of hepatic involvement during COVID-19 infection. Transient elevation of liver enzymes and clotting times may reflect gut barrier defects, triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, the potential clinical consequences of this phenomenon require further clinical observations. We state the absence of a specific profile of parameters’ values which can predict the development of liver damage during or after a COVID-19 infection.