Introduction

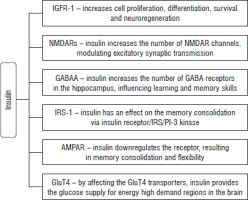

Type 1 diabetes (T1DM) is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood, characterized by insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia. In 2021, there were about 8.4 million individuals worldwide with type 1 diabetes: of these about 1.5 million (18%) were younger than 20 years [1]. The main goal of T1DM patients is insulin therapy to maintain glycemia at an appropriate physiological level and prevent acute and long-term complications. Any glycemic variability leads to either short- or long-term complications. Severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis result in more frequent emergency room visits or hospitalization. Long-term hyperglycemic complications in the form of diabetic micro- and macroangiopathy contribute to many diseases such as cardiovascular disease, nephropathy or neuropathy, which noticeably reduce the life expectancy of the patients [2]. Insulin is a polypeptide protein hormone that is secreted in β cells in the islets of Langerhans located in the pancreas. Apart from its primary function of regulating glucose homeostasis, insulin has been implicated in various neurobiological processes in the central nervous system (CNS), which may influence neurodevelopment and cognitive functions in the pediatric population, including patients with T1DM [3]. Insulin plays a vital role in the signaling pathway that is responsible for memory formation. It is also reported to increase the number of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) and GABA receptors in the plasma membrane, and also downregulates the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors [4]. The first study on the influence of insulin on the CNS is from the year 1954, when radioactive insulin was injected into rats and dogs. The experiment proved that insulin crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) – a discovery that resulted in more studies examining the effect of insulin on the brain [3]. Along with its non-glycemic brain function, insulin also maintains the glucose homeostasis crucial for brain function, as glucose variability may impact the developing neurons through oxidative stress or advanced glycation end products leading to brain cell damage [5]. Insulin also affects the glucose transporters 4 (GluT4) through enhancing their translocation to the cell membrane, allowing for on-demand glucose supply for memory formation. These receptors are highly expressed in regions with high energy demand such as the hippocampus [6].

As an effect on the central nervous system, children with diagnosed T1DM tend to have poorer school performance and may develop specific learning disorders (SLD) more frequently [7]. Diabetes in midlife relates to a 19% decline in cognitive function over 20 years compared to non-diabetic patients [8]. Patients with diagnosed diabetes mellitus (DM) have 54% risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease during the lifetime [9]. There is a wide spectrum of diabetic complications in both the adult and pediatric population. Treating patients with type 1 diabetes using modern technologies such as insulin pumps and controlling glycemia using continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMs) improves self-control and makes it possible to achieve higher durations in target ranges [10]. This reduces the risk of both acute and chronic complications of diabetes, including complications in cognitive functions. The aim of this paper is to review the existing knowledge about the effect of insulin on the CNS and complications of its deficiency in the pediatric population with T1DM.

The role of insulin in brain development

Insulin plays a vital role in brain development from the period of infancy to adulthood. By acting via insulin receptors, it stimulates the growth of the brain tissue. It directs the proliferation, differentiation and growth of neurites [11]. Early childhood is a time of rapid myelination and brain development; approximately 90% of the brain volume is reached by the age of 6 years. There is a difference in white matter growth between the T1DM and non-diabetic children. Lower fractional anisotropy was found in a group of diabetic patients with higher exposure to hyperglycemia. Furthermore, the fractional anisotropy is positively correlated with full scale intelligence quotient (IQ) (p < 0.002) [12]. The cognition scores and brain volumes are negatively correlated with glycemic control, indicating significance of HbA1C and glucose sensor use [5].

Insulin signaling and effect on receptors in the brain

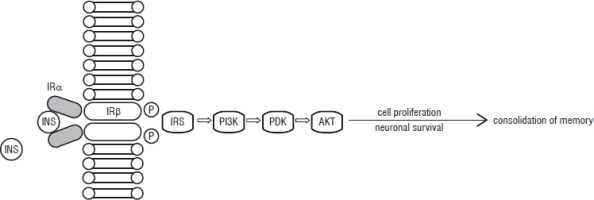

Insulin receptors (IRs) are unevenly distributed in the brain, with the highest expression rate in the olfactory bulb, followed by the cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus and thalamus. Insulin growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), on the other hand, has the highest expression in the region of the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus [4]. Insulin binding to the alpha subunit of the IR triggers the change of the beta subunit to its kinase property, allowing it to become the fully activated tyrosine kinase [13]. This is the beginning of the signaling pathway including insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), PI-3 kinase B (PI3K), phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK), and protein kinase B (AKT) (Fig. 1). The increase of IRS-1 after learning activates PI-3 kinase, which has been linked to memory formation in the hippocampus. Part of the abovementioned pathway has been illustrated by the authors and was inspired by the work of Zhao et al. [14] The mechanism of binding IGF-1 to IGF1R also activates insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which triggers the PI3kinase-Akt signaling pathway (Figure 1) [15]. This is possible due to the high similarity of the molecular structure of insulin and IGF-1, which are said to have a common origin. Although both hormones are assigned to different roles in human body – insulin to glucose homeostasis, IGF-1 to bone elongation or cell division – there is a possible cross-talk between the ligands resulting in a spectrum of activities that both hormones can perform [16].

Figure 1

Insulin signaling pathway [15].

INS – insulin; IR – insulin receptor; IRS – insulin receptor substrate-1; PI3K – PI-3 kinase B; PDK – phosphoinositide-dependent kinase; AKT – protein kinase B

Insulin targets the IR in astrocytes in the brain, influencing the dopaminergic signaling, which may modulate the cognition and mood. The study conducted on mice by Cai et al. revealed that knockout of IR leads to impairment of phosphorylation of tyrosine in Muns18c. It results in decreased release of dopamine and may cause depressive-like symptoms [17]. Insulin has been examined with respect to synaptic plasticity; the results have shown that insulin increases the number of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) channels in the cell surface membrane by regulated exocytosis [18]. NMDAR controls the entry of calcium ions into the cell, triggering long-term potentiation (LTP), which is linked to learning and memory processes [14]. Another important factor in memory formation is the glutamatergic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptor, which is responsible for regulation of fast excitatory synaptic transmission [19]. Long-term potentiation (LTP) increases the number of AMPA receptors , leading to synapse strengthening in neuronal cells. LTP and long-term depression (LTD), which act oppositely, are crucial for maintaining synaptic plasticity [20]. There is also an influence of insulin on activity of AMPA receptors located in the hippocampus. In the CA1 region it results in LTD, downregulating the receptor, which is important in memory consolidation and flexibility [4]. Insulin has also been reported to have an effect on the GABA receptors on either presynaptic or postsynaptic sites. It recruits more of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptors in the plasma membrane by the transition from the intracellular compartment. That can influence the learning and memory skills as GABA receptors are present in the hippocampus [21]. The hippocampus is responsible not only for memory formation, but also for emotional, adaptive and reproduction behaviors. Memory loss is connected to hippocampal cell apoptosis, which can be caused by several factors such as oxidative stress or inhibition of apoptosis regulator genes. In diabetes there is a pro-apoptotic effect which results in decline of neuronal density of the hippocampus, leading to memory loss and cognitive impairment [22]. Insulin has an antiapoptotic effect on the serum depravation-activated apoptosis of cerebral neurons, superoxide (H2O2) retinal neurons apoptosis and corticosterone-induced necrosis of the cerebellum, which highlight the role of insulin as a peptide which helps to combat many neurodegenerative illnesses [23]. A summary of insulin’s effect on the CNS is shown in Figure 2.

Neurological complications of T1DM in pediatric population

Attention disorders

Insulin signaling not only plays a vital role in regulation of metabolism, but also has a significant impact on cognition, mood and behavior. There are many neurological disorders emerging from the deregulated insulin signaling [24]. T1DM leads not only to decreased white matter factor (WMF) and grey matter density but also to psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is characterized by lack of attention, impulsivity and overactivity [25]. According to a meta-analysis by Xie et al., there is a correlation between T1DM and higher prevalence of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) compared to the global population with ASD and ADHD [26]. There is a correlation between the prevalence of ADHD and increased HbA1c level. According to the study by Mazor-Aronovitch et al., the dual diagnosis of ADHD and T1DM manifests in poorer glycemic control. That may lead to more long-term neurological complications and a decreased Diabetes Quality of Life (DQOL) score [27]. Another meta-analysis showed that there is a 35% higher prevalence of ADHD in the T1DM population compared to the healthy population, odds ratio (OR): 1.35 (95% CI: 1.08–1.73). This research also confirmed poor glycemic control in patients with those two comorbidities [28]. All neurological diabetic complications are summarized in Table I.

Table I

Neurological disorders in T1DM children

| Neurological disorder | Study type, size | Diabetic patients’ complications | Mean age (years) | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPG [pmol/l] | MA, > 30,000 | Higher prevalence of ADHD – 5.3% (95% CI: 4.3, 6.4) compared to global 1.2% | < 18 | 2022 | [26] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | MA, >500,000 | 35% higher chance of ADHD in T1DM patients OR 1.35 (95% CI: 1.08–1.73) | < 18 | 2022 | [28] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | MA, > 30,000 | Higher prevalence 1.1% (95% CI: 0.8–1.5) compared to global 0.4% | < 18 | 2022 | [26] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | RS, 372 | Depressive symptoms in 18% of well-controlled diabetic patients and 21% of poorly controlled diabetes patients | 14.2±2.0 | 2014 | [34] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | CST, 102 | Higher depression and anxiety score than healthy population, lower quality of life (p= 0.05) | 8–12 | 2015 | [37] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | CT, 59 | T1DM girl patients are more likely to present depressive symptoms (p= 0.01) than boys | 16.5 | 2023 | [35] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | RT, >15000 | Negative correlation between academic results and HbA1c rs = –0.192, p> 0.001 | < 15 | 2018 | [29] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | RT approx. 15000 | Schooling time shorter by 0.254 years Higher dropout level 7.5% (2.5), p< 0.01 | 12–18 | 2012 | [32] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | CT, 144 | Lower IQ at age of 6, 8, 10, and 12 compared to children without diabetes (p< 0.05) | 7.0–13.6 | 2021 | [30] |

| sRANKL [pmol/l] | MA, 7,500 | Higher risk of epilepsy for < 18-year-olds HR = 2.96 (95% CI: 2.28–3.84; I2 = 0, p= 0.571) | <18 | 2017 | [38] |

Academic results

Taking into consideration the academic performance, the T1DM children tend to have lower academic results. There is a negative correlation between the level of HbA1C levels and academic performance [29]. Along with the lower total volume of the brain, diabetic patients tend to have a lower full-scale intelligence quotients (IQ) score at the ages of 6, 8, 10, and 12 years [30]. Children with episodes of severe hypoglycemia tended to have a lower IQ measure than either group with moderate or non-hypoglycemic events [31]. Students with diagnosed diabetes are more likely to drop out from school than their non-diabetic peers; moreover, diabetics tend to have decreased schooling time [32]. However, a large cohort study from Australia identified no difference in terms of literacy and numeracy between T1DM patients and healthy peers [33].

Depression and anxiety

T1DM pediatric patients have a higher rate of depression; even in well-controlled groups with HbA1c < 7.5%, 18% of them have Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) >13. In a well-controlled group, CDI >13 was correlated with diabetes duration [34]. Depression was found to be more frequent in a group of girls than a group of boys; also there was a higher level of functional problems [35]. Research on the adolescent population revealed mild to moderate anxiety symptoms with a mean score of 9.78 + 5.13 in Generalized Anxiety Disorders 7; also there was a score of 2.75 + 1.76 in Patient Health Questionnaire 2 – a score above 3 indicates major depressive complications [36]. Depression symptoms are more likely to be present in adolescent girls with T1DM than boys (p = 0.010). Higher-level functional problems are positively correlated with higher HbA1c level (p = 0.048) [35]. Another study which compared healthy and T1DM patients aged 8-12 years confirmed a higher depression and anxiety score in the T1DM group; there was also lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL) compared to the control group [37].

Risk of epilepsy

Elevated risk of epilepsy in the long term has not been confirmed to be associated with T1DM. A 2017 meta-analysis conducted by Yan et al. aimed to examine this issue. The study revealed that T1DM adult patients tended to have higher risk of epilepsy, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 3.29 (95% CI: 2.61–4.14; I2 = 0, p = 0.689), whereas the pediatric population had a HR of 2.96 (95% CI: 2.28–3.84; I2 = 0, p = 0.571) [38]. Another recent study showed that adult T1DM patients tended to have 2-to-6-fold higher risk of epilepsy than the general population [39]. Despite the correlation between epilepsy and T1DM, the common patho-mechanism still remains unclear, leaving space for research concerning risk factors [40].

Early treatment and adherence to therapy

One of the key strategies of managing proper neurological development is avoiding hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Monitoring of glucose level in the blood can be achieved by the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) as well as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). Continuous glucose monitoring was found to aid reaching and maintaining desired HbA1c levels. CGM also lowers the prevalence and duration of hypoglycemic events [10]. In a small study on 16 pediatric patients, the influence of CGM was studied. Even though there was no major improvement in glycated hemoglobin levels, a significant improvement was observed in lowering fear of hypoglycemia in both patients and parents [41]. In T1DM patients with depression, it was found that using CSII compared to multiple daily injections (MDI) leads to better results on both the Severity Measure for Depression questionnaire and the Type 1 Diabetes Distress Scale. Patients using MDI have significantly higher depressive symptoms and more diabetes distress compared to CSII patients. Since they can program basal insulin, they have fewer events of hypoglycemia and it is easier for them to exercise. CSII is also advantageous because it has less management- and physician-related diabetes distress [42]. A single-center study conducted on 30 ASD T1DM patients showed that introducing CSII may be beneficial for children with ASD in managing HbA1c levels. In the ASD group, glycated hemoglobin levels did not change after CSII implementation, while in the control group of ASD patients without CSII, the HbA1c levels increased. This study outlined the beneficial effect of using CSII in T1DM ASD patients in HbA1c level maintenance. [43] A rather recent and promising approach is the implementation of a hybrid closed-loop (HCL) insulin delivery system which can adjust the basal insulin delivery to set glucose target options in response to CGM readings [44]. When compared with a group of standard care (either MDI or open loop system), the hybrid closed-loop group displayed a significantly greater increase in regional grey matter volumes and cortical surface area, but no difference in total grey and white matter volume or cortical thickness was observed. Moreover, the hybrid closed-loop group had higher standardized IQ scores. After 6 months of use, the closed loop group had fewer recorded events of hyperglycemia and less glucose variation. However, what is most important is the time in range (TIR), as patients from both arms of the study with higher nighttime TIR (>37%) showed the greatest improvements in the Perceptual Reasoning Index (P = 0.009) and cortical surface area [45]. The abovementioned studies show the importance of proper glycemic control and its influence on the developing brain.

Another important approach is implementation of cognitive therapy and psychological help. In the first two years after diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes, children experienced double the amount of depression and adjustment problems compared to their peers [46]. Cognitive behavioral therapy appears as a possible solution since it not only helps in managing depression but also aids glycemic control when compared to non-directive support counseling (NDC). In a multi-center study conducted in the UK, adolescents who underwent CBT therapy for 12 months showed maintained or improved HbA1c (72 mmol/mol before and 73 mmol/mol after 12 months; p = 0.51) while patients’ HbA1c results in the NDC arm of the study deteriorated (from 68 to 78 mmol/mol; p = 0.001). These results highlight the better glycemic control in patients under cognitive behavioral therapy due to depressive symptoms [47].

Summary

Insulin plays a vital role in the human brain; it takes part in the insulin signaling pathway responsible for memory consolidation and increases the GABA receptors in the hippocampus, the part of the brain known for long-term memory formation. Insulin deficiency leads to diabetic neurological complications, which seem to be a significant problem among not only elderly people but also for the pediatric population. This review summarized the existing knowledge about neurological complications of the pediatric diabetic population. Compared to the general population there is higher prevalence of ADHD, ASD, seizures, and depression among diabetic children. Diabetic patients tend to have lower IQ scores and lower academic results. Maintaining sufficient TIR seems to be the most accurate way of preventing long-term neurological complications of the pediatric population. The promising outcomes of continuous glucose monitoring and hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery require further research in the future, especially in patients diagnosed with ASD and ADHD.

ENGLISH

ENGLISH