Introduction

Aldosterone as the principal mineralocorticoid hormone in humans, synthesized predominantly in the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex, plays a crucial role in maintaining electrolyte balance by regulating sodium absorption and intravascular volume, as well as potassium excretion, via the distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts of the kidneys [1–4]. Its biosynthesis involves several enzymatic steps, with the final three reactions being catalyzed by aldosterone synthase, a mitochondrial cytochrome P450 enzyme encoded by the CYP11B2 gene located on chromosome 8q24.3 (Fig. 1) [1–5]. Aldosterone synthase facilitates the conversion of deoxycorticosterone (DOC) to aldosterone through sequential steps: 11β-hydroxylation of DOC to form corticosterone, 18-hydroxylation of corticosterone to form 18-hydroxycorticosterone (18OHB), and finally, 18-oxidation of 18OHB to produce aldosterone [1–4]. Pathogenic variants in the CYP11B2 gene manifest clinically as isolated congenital primary hypoaldosteronism and can lead to two forms of aldosterone synthase deficiency (ASD): type 1 (ASD1), also known as corticosterone methyloxidase type I deficiency (CMO I), where both hydroxylation and oxidation processes are impaired and type 2 (ASD2), also known as corticosterone methyloxidase type II deficiency (CMO II), where only the oxidation process is impaired [4, 6–9]. Aldosterone synthase deficiency type 1 is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by an impaired aldosterone synthesis and mineralocorticoid deficiency symptoms, which is often caused by homozygous pathogenic variants, impacting heme-binding sites or highly conserved sites necessary for enzymatic activity [1, 2, 4, 5, 9]. Contrastingly, in ASD2 more complex genotypes are observed, including double homozygosis, compound heterozygosis, and triple variants, which are more likely to cause partial enzyme inactivation [9]. Both diseases have a distinct biochemical profile. In CMO I all three enzyme activities of aldosterone synthase are severely impaired or abolished. While corticosterone is still synthesized due to the activity of 11β-hydroxylase, the other deficiencies lead to a defect in the 18-hydroxylation of corticosterone to 18OHB, which results in increased levels of 18-hydroxy-11-deoxycorticosterone (18OHDOC), reduced levels of 18OHB, an increased corticosterone to 18OHB ratio and low to undetectable aldosterone levels [1, 2, 5]. In contrast, CMO type II is caused by pathogenic variants that specifically impair the 18-oxidase activity, while retaining both the 11β-hydroxylase and 18-hydroxylase activities, resulting in low aldosterone levels, markedly elevated levels of 18OHB and 18OHDOC, and an increased 18OHB to aldosterone ratio [1, 2, 5, 10]. The ratio of 18OHB to aldosterone may thus be useful to differentiate between the two disorders: < 10 in type I and > 100 in type II. However, the distinction between CMO types is not always clinically useful, as the genotype-phenotype correlation in CMO may not be straightforward. Cases have been reported where patients exhibit biochemical features intermediate between CMO types I and II, or where the phenotype does not correspond with the expected genotype [1, 4, 5]. Moreover, some authors suggest that the division between ASD1 (CMO I) and ASD2 (CMO II) may be unclear, therefore they imply that this distinction should no longer be used and other genes should be analyzed to explain the previously observed biochemical differences [9]. In spite of these genetic and biochemical differences the clinical manifestation of ASD1 and ASD2 is identical, and stems from aldosterone deficiency, leading to excessive sodium excretion and potassium retention in the renal distal tubule and cortical collecting duct [11]. Typically, ASD presents in infancy with life-threatening electrolyte imbalances, including hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, metabolic acidosis, and elevated plasma renin activity, while aldosterone levels are low or undetectable [1–5]. Clinically, affected infants often exhibit failure to thrive, vomiting, severe dehydration, and poor growth [1–5, 10]. Older children and adults may have normal serum electrolytes and plasma renin activity, even if left untreated, highlighting the age-variability of clinical manifestations, most probably due to increased sensitivity of the mineralocorticosteroid receptors [3, 10, 12]. Differential diagnosis of CMO is challenging due to overlapping clinical features with other diseases resulting in impaired adrenal steroidogenesis: congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 (PHA1) [2, 3, 10]. Accurate diagnosis of CMO is critical, as affected infants may succumb to severe salt wasting and hyperkalemia if not recognized and treated promptly [3, In this study, we aim to investigate the rare case of hypoaldosteronism due to aldosterone synthase deficiency in a 15-year-old female, diagnosed in the neonatal period following electrolyte imbalances and subsequent genetic testing. The study was approved by Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland (No. approval: 1072.6120.120.2022).

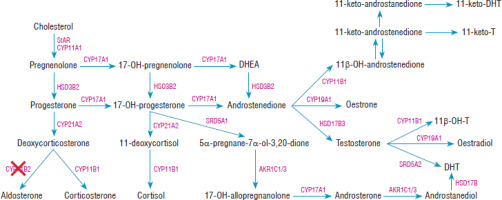

Figure 1

The steroid synthesis pathway. CYP11B2 – aldosterone synthase enzyme was marked with a red cross. Based on El-Maouche et al. [21]

Case report

The female patient was born preterm at 35 weeks of gestation to a mother with a history of two pregnancies, including one miscarriage, and delivered spontaneously via vaginal birth. The recorded birth weight was 4,200 g. At approximately two weeks of life, during a routine visit to a primary care center, a significant weight loss of 12.4% was noted, and a suspicion of urinary tract infection was raised. The infant exhibited significant regurgitation, lethargy, poor responsiveness, inadequate feeding, and noticeable skin hyperpigmentation. She was subsequently admitted to a local hospital, where a 1.5-week hospitalization revealed failure to gain weight, electrolyte abnormalities, and clinical suspicion of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Initial treatment included a single dose of prednisolone (5 mg) on the 25th day of life, intravenous hydrocortisone (2 × 18 mg), and intravenous fluids composed of a 1 : 1 mixture comprising 50 ml of 5% glucose and 50 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride. At 26 days of life, the infant weighed 3,680 g. The neonate was fed Bebiko 1 formula, receiving 40–60 ml per feeding, 7 to 10 times daily. There were no episodes of vomiting, and the infant passed one normal stool per day. On examination, the infant appeared in generally good condition but exhibited poorly developed subcutaneous fat, giving the impression of darker skin tone, along with a few oral mucosal lesions and dry oral mucosa, particularly of the tongue. Laboratory findings included hyponatremia (serum sodium 128 mmol/l), and hyperkalemia (potassium 6.41 mmol/l), with elevated hemoglobin and hematocrit. The patient was referred for further diagnostic workup and management to the Neonatal Unit of the Newborn Department and the Pediatric Endocrinology Ward at the University Children’s Hospital in Krakow, where she was hospitalized from the 28th day to the 49th day of life. Her weight was noted to be 3,720 g at admission and 3,900 g at discharge, with a recorded length of 52 cm. On admission, the infant presented with cyanosis, decreased skin turgor indicative of dehydration, and abnormal swelling of the lower extremities. Restlessness was also noted. Initial laboratory evaluation revealed hyponatremia (serum sodium 131.2 mmol/l) and hyperkalemia (serum potassium 6.5 mmol/l). Intravenous rehydration was initiated with 250 ml of a 1 : 1 mixture comprising 125 ml of 5% glucose and 125 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride. Over the subsequent days, recurrent episodes of hyponatremia were observed, with serum sodium levels dropping to as low as 129 mmol/l during attempts to taper intravenous fluids. Treatment was supplemented with 0.5 ml of 10% NaCl added to each of 7–10 daily feedings. A comprehensive endocrine reassessment yielded the following results: aldosterone of 151.7 pg/ml (N: < 1,035), plasma renin activity (PRA) greater than 50.0 ng/ml/h (N: 2.35–37.0), ACTH of 9.3 pg/ml (N: 10–60), cortisol of 168.5 ng/ml (N: 50–170), TSH of 3.59 µIU/ml (N: 0.8–9.1) and FT4 of 17.2 pmol/l (N: 10.0–25.0). It was concluded that the hyperpigmentation was not due to ACTH excess but instead might have been related to dehydration or loss of subcutaneous fat. A 24-hour urine steroid profile analysis was performed at 5 weeks of age leading to the diagnosis of aldosterone synthase deficiency type I (Table I). During hospitalization, the patient’s laboratory test results (Table II) were closely monitored, revealing fluctuating electrolyte levels and a failure to gain weight. At 43 days of life, the patient was started on fludrocortisone therapy (Cortineff) at a dose of 0.025 mg once daily, which was increased to 0.075 mg five days later; this intervention resulted in the normalization of sodium and potassium levels, rapid weight gain, and overall clinical improvement.

Table I

The patient’s twenty-four hour urine steroid profile (GC/MS) at 5 weeks of age

[i] An – androsterone; Et – etiocholanolone; 11-OAN/ET – 11-ketoandrosteron/etiocholanolone; 11-OHAN – 11-hydroxy-androsterone; 11OHET – 11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone; DHA – dehydroepiandrosterone; 5-AND – 5-androstendiole; 16a-OHDHA – 16a-hydroxy-DHA; An-3-ol-5 – androstentriole; 5PT – 5-pregnenetriol; 16-OHPN – 16 α-hydroxy-pregnenolone; 17OHPN – 17-hydroxy-pregnanolone; PT – pregnanetriol; PTN – pregnanetriolone; PD – pregnanediol; E1 – estron; E2 – estradiol; E3 – estriol; THS – tetrahydro-11-deoxycortisol; THDOC – tetrahydro-11-deoxycorticosterone; THA – tetrahydro-11-dehydrocorticosterone; THB – tetrahydrocorticosterone; THAldo – 3a,5b-tetrahydroaldosterone; THE – tetrahydrocortisone; THF – tetrahydrocortisol; a-CTN – a-cortolone; b-CTN – b-cortolone; a-CT – a-cortol; b-CT – b-cortol; E – cortisone; F – cortisol; 6b-OHF – 6b-hydroxycortisol, 20a-DHF – 20α/β-dihydrocortisol.

Table II

Daily changes in electrolyte levels during hospitalization. Data from the Regional Hospital are highlighted in blue, data from the University Children’s Hospital in Krakow – are shown in green, on the 43th day of life fludrocortisone therapy was introduced (dark green)

The gradual normalization in specific hormonal parameters-evidenced by a PRA of 20.12 ng/ml/h at 2.5 months – alongside normalization of laboratory tests (Na+ 141 mEq/l, K+ 4.42 mEq/l at 4 months of age) during the subsequent follow-up visits confirmed effective disease control. By the 1st year of age, the hormonal parameters had further improved, showing a PRA of < 0.2 ng/ml/h and an aldosterone level of 15.5 pg/ml. Moreover, a stable electrolyte profile was maintained at 2 years and 9 months of age (Na+ 141 mEq/l, K+ 4.45 mEq/l, Cl– 106.3 mEq/l).

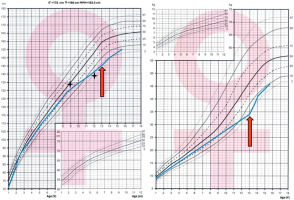

Over a follow-up period of 14 years, despite appropriate treatment, the patient experienced delayed puberty and began presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, and delayed growth, which prompted an investigation for celiac disease. Positive serology for tissue transglutaminase (tTG) IgA antibodies confirmed the diagnosis, and the patient has maintained a strict gluten-free diet for the past 1.5 years. The Centile chart for body mass and height is shown in Figure 2. At 15 years of age, she remains premenarchal and was referred for further genetic and hormonal evaluation.

Figure 2

Growth charts based on Palczewska and Niedźwiedzka percentile grids. Bone age assessments are marked with fourpointed stars. The orange arrow indicates the moment of celiac disease diagnosis, demonstrating its temporal relationship with the observed growth pattern

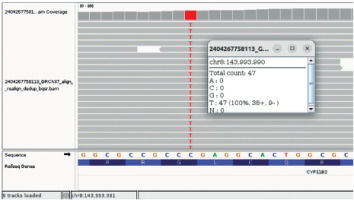

The patient`s karyotype was 46 XX. Genetic testing using next-generation sequencing (NGS) identified a pathogenic homozygous variant in the CYP11B2 gene (c.1354G>A), known for causing aldosterone synthase deficiency type I. Next-generation DNA sequencing reads of the CYP11B2 gene from the patient are presented in Figure 3. Figure 4 presents the results of automated DNA sequencing for CYP11B2, demonstrating that both the paternal and maternal sequences harbor the same pathogenic variant, ENST00000323110.2:c.[1354G>A];[1354G=], corresponding to the protein change ENSP00000325822.2:p.[(Gly452Arg)];[(Gly452=)]. This confirms that our patient inherited the identical pathogenic variant from both parents, resulting in a homozygous genotype. The patient’s parents come from neighboring small communities and are not consanguineous; however, the genetic analysis suggests the likelihood of a common ancestor.

Figure 3

Identification of a pathogenic variant in CYP11B2 gene. Nextgeneration DNA sequencing reads of the CYP11B2 gene from the patient aligned to the reference sequence are visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)- NM_000498.3(CYP11B2): c.1354G>A|p.Gly452Arg. Chr8-143’993’990 C>T

Figure 4

Sanger (automated) DNA sequencing chromatograms of the CYP11B2 gene illustrating that both the paternal (upper chromatogram) and maternal (lower chromatogram) sequences are heterozygous for the same pathogenic variant, ENST00000323110.2:c.[1354G>A];[1354G=], which corresponds to the protein change ENSP00000325822.2:p. [(Gly452Arg)];[(Gly452=)]. Frames indicate the position of the variant in both chromatograms, confirming that the patient inherited this pathogenic variant from both parents, resulting in a homozygous genotype

Currently, the patient maintains a long-term regimen that includes 0.025 mg of fludrocortisone (Cortineff) on alternate days, 2,000 IU of vitamin D3 daily, and calcium supplementation at 500 mg daily. As discontinuation of fludrocortisone therapy effected in fatigue and school troubles, patient requires mineralocorticoid supplementation, with higher doses during hot weather. In addition to her endocrine management, she continues to adhere to a gluten-free diet for her confirmed celiac disease and receives regular evaluations from both endocrinology and dietary specialists, with genetic counseling provided to the family to assess the risk of similar conditions in potential future siblings.

Discussion

In this study we present a case of a female patient diagnosed with CMO I, firstly confirmed by steroid profiling and then genetic analysis, which revealed a homozygous nonsense pathogenic variant in the CYP11B2 gene (c.1354G>A). The patient exhibited classic features of CMO I in infancy, including electrolyte disturbances, failure to thrive, and vomiting, and responded well to mineralocorticoid replacement therapy with fludrocortisone. It is wildly reported that the condition’s severity usually tends to decrease with age, and is frequently resolved by adulthood, as dietary salt intake increases after infancy and sensitivity to mineralocorticoids improves [2, 13]. This might also be the result of a progressive decrease in the need for aldosterone to maintain electrolyte balance, which could be aided by alternate ACTH-dependent pathways for mineralocorticoid production, as well as compensatory mechanisms outside the adrenal glands [15]. Orthostatic hypotension and hyperkalemia, however, can still occur in adults in specific circumstances, such as a heatstroke or dehydration [15]. While salt supplementation was discontinued in infancy, fludrocortisone is still used in order to lessen the consequences of aldosterone shortage, with increased dosing required during the heat waves.

However, despite adequate treatment and normal electrolyte concentrations, around the age of 9 patient’s growth and weight gain began to be inhibited and later delayed puberty was also observed. This may have been in line with other literature sources reporting persistent growth retardation in spite of electrolyte normalization [11]. Yet, one must always consider possible conditions coexisting with the principle disease and perform a thorough differential diagnosis. In our case, it resulted in the diagnosis of celiac disease at 15 years of age. We concluded that the persistent requirement of mineralocorticoid supplementation and electrolyte disturbances may have been linked to the escape of ions through the digestive tract due to its mucosal damage. Given the fact that intestinal healing usually takes 6 to 24 months, we hope that our patient who has maintained a gluten-free diet for 1.5 years, will in time become independent from mineralocorticoid supplementation [14].

In case of electrolyte imbalance such as hyponatremia and hyperkalemia with coexisting symptoms of salt-wasting syndrome such as vomiting, dehydration and failure to thrive, insightful and precise diagnosis including genetic tests and twenty-four hour urine steroid profiling is essential due to the different therapeutic approaches recommended depending on the etiology of the symptoms. For instance, in ASD fludrocortisone in combination with NaCl is used, in the case of pseudohypoaldosteronism only large amounts of NaCl would be advised, while salt-wasting CAH requires both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid supplementation, often alongside NaCl [5]. Salt supplements (10% NaCl) are frequently necessary for electrolyte management in patients with CMO I, especially in the early stages when dietary salt consumption is limited [2]. Although fludrocortisone remains the primary treatment, exploring alternative approaches, such as modulating the renin-angiotensin system, could lead to better long-term outcomes. Future studies should aim to identify novel genetic variants beyond CYP11B2, evaluate the potential of gene therapy, including CRISPR-Cas9, as a treatment for CMO type I, and investigate the long-term cardiovascular and metabolic risks in adults with this condition [16]. ASD1 prevalence has not been unequivocally determined in recent studies. The condition’s epidemiology is still poorly understood, and more research is required [2]. Although it’s precise prevalence is unknown, it is estimated to be far less common than CAH [4]. According to the MalaCards – the human disease database, there are currently 156 described ClinVar variants in the CYP11B2 gene [17]. However CMO I is more commonly found in families with consanguinity due to a homozygous variant, it can also be present in unrelated families, as demonstrated in 56 out of 62 cases reported by Merakou et al. [5]. According to the currently available information, the disease is most common among specific groups of people, especially Jewish communities. In Portugal and Greece, as well as among Asian communities, such as Arabs, Indians, Japanese, and Chinese, cases have also been documented [2, 5, 15, 18].

A comprehensive review of the available medical literature reveals no studies specifically examining a correlation between CMO I and celiac disease. Currently, there is also no evidence to support a direct link between these conditions.

A review of the literature indicates that clinical presentation of aldosterone synthase type I deficiency (CYP11B2 mutations) varies predominantly with age, and only limited evidence supports consistent genotype–phenotype correlations [1–11, 15, 18]. Growth retardation despite normalized electrolyte levels, persisting throughout childhood, has been observed in several previously reported patients, including our own case, but no specific pathogenic variants have been consistently associated with this phenotype [11]. Interestingly, neurosensory hearing loss has been described in a patient with a pathogenic variant of CYP11B2 (p.Thr318Met, c.953C>T), potentially related to the role of aldosterone in the electrolytic homeostasis of the endolymph [9, 20].

As noted by White et al. [11], distinguishing true genotype–phenotype relationships in this disorder is challenging, as the severity of clinical manifestations often diminishes with age, potentially masking underlying correlations.

Conclusions

This study documents the first occurrence of CMO I with celiac disease in the first genetically confirmed Polish case. Genetic analysis revealed a novel homozygous pathogenic variant in the CYP11B2 gene (c.1354G>A; p.Gly452Arg). Despite the homozygous nature of the variant, it was inherited from non-consanguineous parents, which highlights the importance of recognizing potential genetic risks in rural, isolated communities. Additionally, the concurrent development of celiac disease in this patient emphasizes the possibility of coexisting comorbidities that can adversely affect growth. The lack of research in this area highlights a gap in the literature, indicating that any potential association has not yet been a focus of scientific investigation. Finally, given that neonatal hyponatremia is a life-threatening condition requiring immediate attention, it is critical that CMO I despite very scarce occurrence should be considered in the differential diagnosis of affected neonates.

ENGLISH

ENGLISH